In any passion or hobby, there are aspects we don’t enjoy as much as others. In jewelry, the technical parts can feel intimidating. For instance, pins have evolved so much in just the past century that you might feel lost when researching what type of pin back you should use for your next masterpiece. With this guide, we hope to alleviate that stress by detailing the different types of pins, their uses and how to make (or buy) them.

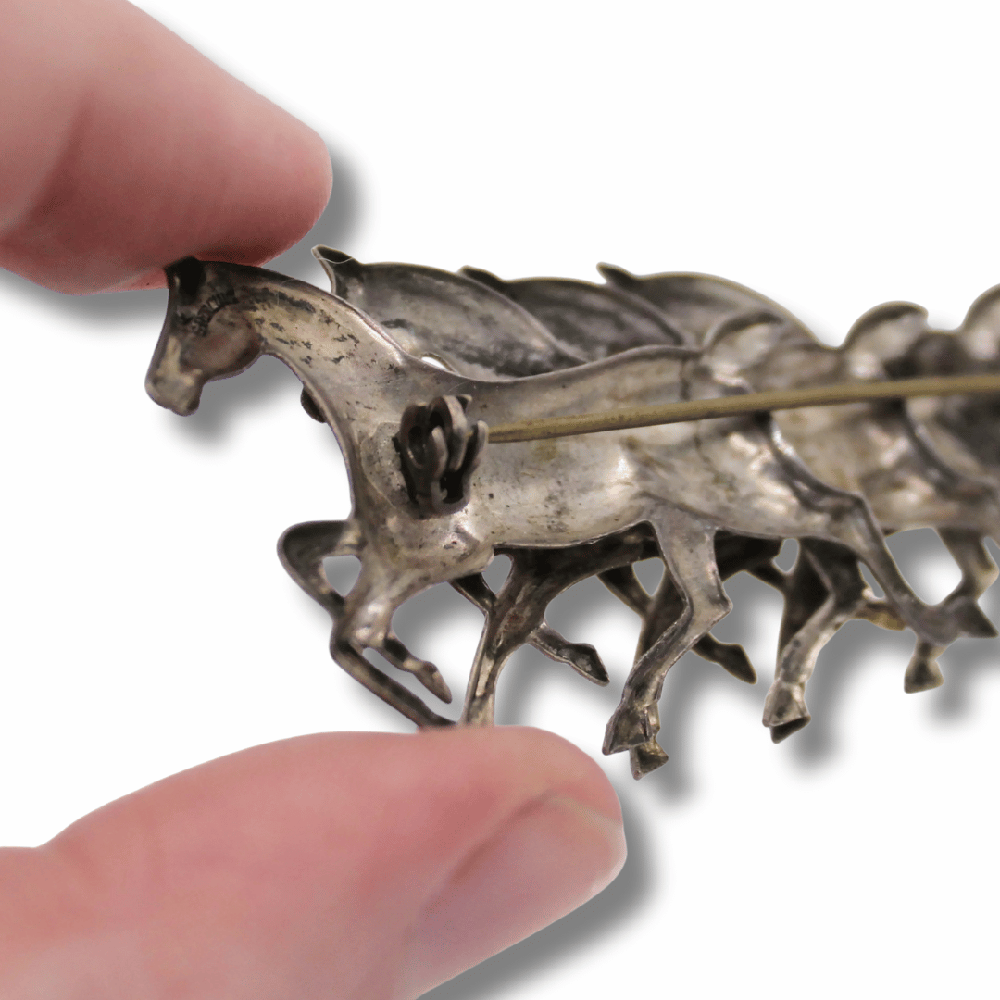

Brooch Pin or Fibula

As one of the oldest accessories in history, the brooch–also known as a fibula–was only functional at first, made to secure cloaks and sleeves. Commonly made of brass or bronze, this pin maintains a simple design. It was the most common form of pin during the industrial revolution and into the 20th century, though it fell to the wayside after the creation of the butterfly clutch.

It started as a sturdy needle set tightly against the brooch, leaving little room for jostling, but we eventually began incorporating hooks, and later clasps, for further security. In many Victorian-era brooches, the clasp that holds the needle in place was sometimes embellished as a spiral. The brooch allows for endlessly creative pin design, since it's not limited by the size or shape of the design.

Long Pin or Needle Pin

The long pin or needle pin is a long stick pin, often (but not always) accompanied by a safety stopper on one end. They’re most often used to secure large accessories like head scarves, ties, and hats in place. Traditionally, one end has a decorative handle similar to a hair stick, though many jewelers also make decorative stoppers and patterned sticks.

Butterfly Clutch or Tie Tack Clutch

As an easily accessible pin clasp favored for its ease and reliable security, the butterfly clutch–also known as a tie tack clutch–was a revolutionary invention in the world of jewelry and fashion. There are two “wings” on either side of the clasp that can be pinched together to remove and secure the back onto a small needle. The clutch led to new jewelry innovations like tie pins, lapel chains and the flat enamel pins we see today.

We do not suggest attempting to make your own clutches. There are a small number of successful and dependable clutch manufacturers that sell their clasps in the dozens and even thousands through major retail outlets like Amazon and Walmart–though as a small business ourselves, we recommend checking out your local craft shops. Clutches come in copper, brass, silver, and even gold.

Rubber Clutch

The rubber back is potentially the most popular type of pin back in the 21st century, surpassing its sister, the butterfly clutch, in recent years. You’d be most likely to see this type of pin back for most contemporary enamel pins. Comparatively, the rubber back and the butterfly clutch are evenly matched. They seem to be about the same price, neither is truly more secure than the other and they’re still easier to outsource than to make yourself. The only real difference is comfort and backing. The rubber backing is less irritating when worn and easier to remove than the butterfly clutch. However, it’s not as versatile as the clutch. We suggest adding a flat back to your designs so that the rubber back can slide snugly against it.

Locking Pin Back

If you’re looking for something invincible for your pins, the locking pin–the most recent successor to clutches–takes the lead in security. A spring mechanism in the lock prevents accidental removal, locking it in place; hence the name. However, these pin backs are rather bulky and a touch more expensive. They’re best used in securing decorative pins to thick textiles like denim or leather.

Cuff Link

Like many fashion trends, the cuff link was popularized by royalty. Before King Charles II flaunted his ornamental cuff buttons, men’s shirt cuffs were usually secured by simple buttons or ribbons. By the 20th century, cuff links were practically required for businesswear. They were so important that companies like Larter & Sons were founded for the exclusive purpose of designing men’s cuff links.

The cuff link was designed to be affixed to the button holes on shirt cuffs, making them unlike other accessory pins, which necessitate needles. The exact style of backing can vary, but usually there’s a bar–often movable, though sometimes static–that can turn and twist through the hole, where it can secure the fabric between the bar and the design. Any flat or shallow design between ½” and ⅞” in width and length can make a cuff link, which means impression dies for buttons and small lockets can be converted for this use.

Clip Pin

If you’re familiar with tie clips, fabric clips, and even certain barrette styles, you know what a clip pin looks like. It superseded the tie pin, a functional accessory of the 19th century that was somewhat incompatible with the popularization of the suit tie–stabbing a needle through the centerpiece of an outfit was not an imperfection 1920s tailors would allow.

The clip consists of a hinge and two long bars, which a piece of fabric is slipped between, allowing one to secure the tie without marring the fabric in a manner similar to a bobby pin. Clip pins can certainly be made yourself (as long as you’re not intimidated by using hinges). They’re great candidates for repurposing our patterned band and antique bar pin impression dies.